Southern ocean current faces slowdown threat

|

The impact of global warming on the vast Southern Ocean around

Antarctica is starting to pose a threat to ocean currents that

distribute heat around the world, Australian scientists say, citing new

deep-water data.

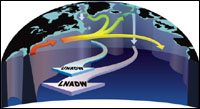

Melting ice-sheets and glaciers in Antarctica are releasing fresh water, interfering with the formation of dense "bottom water", which sinks 4-5 kilometres to the ocean floor and helps drive the world's ocean circulation system.

A slowdown in the system known as "overturning circulation" would affect the way the ocean, which absorbs 85 percent of atmospheric heat, carries heat around the globe.

"If the water gets fresh enough ... then it won't matter how much ice we form, we won't be able to make this water cold and salty enough to sink," said Steve Rintoul, a senior scientist at the Australian government-funded CSIRO Marine Science.

"Changes would be felt ... around the globe," said Rintoul, who recently led a multinational team of scientists on an expedition to sample deep-basin water south of Western Australia to the Antarctic.

Water dense enough to sink to the ocean floor is formed in polar regions by surface water freezing, which concentrates salt in very cold water beneath the ice. The dense water then sinks.

Only a few places around Antarctica and in the northern Atlantic create water dense enough to sink to the ocean floor, making Antarctic "bottom water" crucial to global ocean currents.

But the freshening of Antarctic deep water was a sign that the "overturning circulation" system in the world's oceans might be slowing down, Rintoul said, and similar trends are occurring in the North Atlantic.

For the so-called Atlantic Conveyor, the surface warm water current meets the Greenland ice sheet then cools and sinks, heading south again and driving the conveyor belt process.

But researchers fear increased melting of the Greenland ice sheet risks disrupting the conveyor. If it stops, temperatures in northern Europe would plunge.

Rintoul, who has led teams tracking water density around the Antarctic through decades of readings, said his findings add to concerns about a "strangling" of the Southern Ocean by greenhouse gases and global warming.

Australian scientists warned last month that waters surrounding Antarctica were also becoming more acidic as they absorbed more carbon dioxide produced by nations burning fossil fuels.

Acidification of the ocean is affecting the ability of plankton -- microscopic marine plants, animals and bacteria -- to absorb carbon dioxide, reducing the ocean's ability to sink greenhouse gases to the bottom of the sea.

Rintoul said that global warming was also changing wind patterns in the Antarctic region, drawing them south away from the Australian mainland and causing declining rainfall in western and possibly eastern coastal areas.

This was contributing to drought in Australia, one of the world's top agricultural producers, he said.

Source: Reuters News Service