Exploring the ancient grasslands of Madagascar

By William Bond, Chief Research Scientist, SAEON

|

|

MADAGASCAR ... a magical word for biologists.

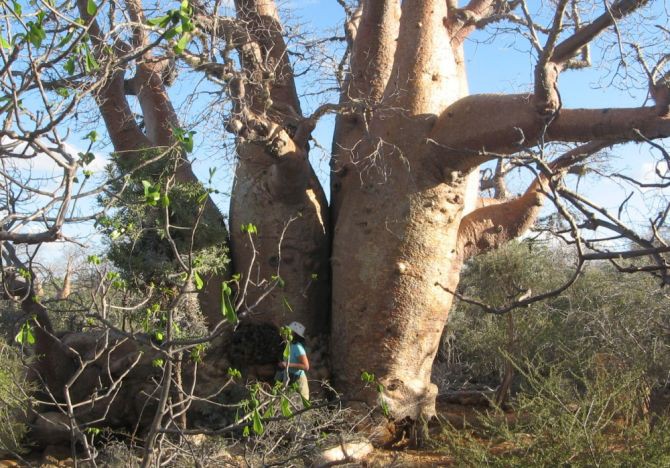

It is a mini-continent, the world’s 4th largest island, so close to Africa yet so different in its extraordinary lemurs, reptiles, birds and its remarkable diversity of plants including some of the strangest growth forms you will ever see.

I first visited the island in 2006 with John Silander, an ecologist from the University of Connecticut, and Joel Ratsirarson and Jeannin Ranaivonasy from the University of Antananarivo in Madagascar. We visited the 'spiny’ forests of the south looking for the legacy of the giant elephant birds. Though the birds are extinct, their legacy persists in plants designed to defend themselves against bird browsing and fruits designed for transport by the birds.

But that is another story.

‘Brand new’ Madagascan grasslands? Or ancient grasslands dating to Africa’s great grass revolution?

I was also keen to see Madagascan grasslands. Madagascar’s wildlife is concentrated in the forests. But the big surprise is that more than 75% of the island is covered in grass. For over a century, the grasslands have been interpreted as degraded secondary vegetation created by burning and felling of the pristine forests after people first settled the island about 2000 years ago.

I was intrigued to see what a brand new grassland looked like (2000 years is ‘brand new’ in ecological terms). I expected a biological desert - the kind of ecosystem created when alien species invade a pristine ecosystem devastating the native community and replacing it with just a few species dominating over vast areas.

But this is not what we found.

Instead, the grasses were surprisingly diverse with up to a dozen species at any spot and comparable to, say, South African Highveld grasslands. The species also changed from one locality to the next and across climate and habitat gradients. We even saw grazing lawn species unique to Madagascar, perhaps a legacy of the extinct hippos.

The central highlands are strikingly reminiscent of grassland country in eastern South Africa with rolling green hills in the growing season, golden in the dry season, or black from the many fires. From literature reviews, we found that Madagascar has a grassland flora with hundreds of grass species many of which are found only on the island. Indeed grasses make up a similar fraction of the floras of both these biodiverse countries. There are also birds, snakes, lizards, ants and termites restricted to grassy habitats.

This is not what you would expect in ‘brand new’ grasslands created by clearing forests. We wrote a review of grassland biodiversity suggesting that the grasslands were ancient, part of the great grass revolution experienced by Africa and other continents several million years ago.

The powerful deforestation narrative has, over the last hundred years, led to extreme neglect of Madagascan grasslands as subjects of ecological research, conservation consideration, and reserve design and management. But if you accept the grasslands as being part of Madagascar’s unique biological legacy, then they demand attention.

Towards ecological understanding

Through funding from the McArthur Foundation, we were able to develop a training course with colleagues from the University of Antananarivo, the University of Connecticut and the University of Cape Town.

The African experience was particularly useful for starting a new programme on grasslands. We were able to transfer South African ecological understanding, management practices, and burning policies and practices to our colleagues and to students in Madagascar for their consideration. I have participated in two courses and associated field and research trips, most recently representing SAEON in October 2014.

Exploring Madagascan grasslands has been fascinating. How do you answer the critical question of the age of a biome? How do you document the diversity of the system over the whole vast island?

|

|

How do you switch from suppressing fires to lighting them in a grassland/forest mosaic? Without fire, the grasslands become moribund, with fire, the forests are destroyed. How do you persuade managers of conservation areas, trained for generations to suppress fires, and backed by national legislation, to start burning? What clues can you use to test whether forests have long been fragmented as patches in a sea of flammable grass, or are sad remnants of a once-continuous primeval forest? How can you identify ancient, old-growth grasslands, from those created by recent deforestation which should be prime targets for reforestation? How will the forest/grassland balance change with changing climates as Madagascar has been experiencing over the last two decades?

|

Back to the roots

Our Malagasy colleagues are faced with a daunting challenge of, essentially, learning about grasslands from scratch. But in the past few years, great progress has been made. Together with scientists from Kew, the grass flora is being re-evaluated (for the first time in decades), field surveys are being conducted, new grassland-centred conservation areas have been established, palaeoecological studies are in progress, and new studies have been initiated on the ecology of grasslands and fire.

Besides the excitement of being part of these activities, I have enjoyed the intellectual jolt of comparing Madagascan and African grassy ecosystems. The stimulus of trying to understand this very different place makes me look at my familiar South African grasslands with new, wide-open eyes.

Return to Index