Adrift in a sea of information: how can we be better (marine) science communicators?

|

|

Do you ever feel overwhelmed by the sheer volume of information available online? The pace at which communication platforms appear, disappear, become popular, or fall by the wayside?

Do you blog, vlog, snap, insta, tweet, update, share, or go live about your science?

No? You should - or at least you should seriously consider it. “To do less is a moral failure of science and academia” - Jonathan Foley, 2016.

Science communication, by definition (according to Google) “generally refers to public communication presenting science-related topics to non-experts”. The words in that definition that are most important to me are “public communication” and “non-expert”.

I think it’s fair to say that most scientists are familiar with the feeling of terror you get when Granny or Aunt Mavis wants to know exactly what it is you DO. Thoughts fly through your head and all you seem to be able to say are big words that no one else is interested in. Then, after your stuttered, jargon-heavy reply to Granny, she will persist in asking “But what is that good for?”, and then you really have to explain very nicely.

That working definition leaves a lot to be desired, because it makes public communication seem deceptively simple. Just get out there and communicate, right? Unfortunately, no. Recent studies have shown that people, and especially young people, are becoming less able to differentiate between real news and fake news, and advertisement-based content versus fact, and of course, evidence-based science and pseudoscience.

One of the defining phenomena of the present times reshaping the world as we know it, is the worldwide accessibility to the Internet – Statista (The Statistics Portal)

The sheer amount of information available to the everyday user (by 2020, three BILLION people will be online), plus the ever-shrinking toolbox of critical thinking skills, means that we find ourselves fighting just to be heard over all of the white noise that essentially fills the Internet. It is not enough, anymore, to simply communicate; communication must be effective and intentional.

Communicating science in the 21st century has greater relevance than ever before. We find ourselves at a tipping point in history - our resource depletion crisis is forcing a paradigm shift, but our information abundance is keeping that shift from being effective. The onus of effective communication is not on the end of the receiver, but on the end of the giver. It is up to us to cut through the input stream in order to reach our audience.

|

Yes, I said that. Literally. It is YOUR responsibility, among all the other responsibilities of your work and your position as a scientist (or researcher, or student, or technician, or manager) to communicate with the outside world.

In early December 2016, I was privileged to attend CommOCEAN 2016, the 2nd International Marine Science Communication Conference, and present a plenary address in Bruges, Belgium. The conference was opened by Vladimir Ryabin (Executive Secretary of the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO), Sigi Gruber (Head of the Marine Resources Unit at DG Research and Innovation, European Commission), and Jan Mees (Chair of the European Marine Board & Director of the Flanders Marine Institute). Between the three of them they mentioned the following extremely salient points:

- It is time for change in the way we communicate about science.

- Science communication is no longer a privilege, but an obligation.

- Science communication is becoming a commitment of institutions, and a requirement of funding bodies.

|

The first step is to take the plunge and embrace social media and online platforms. In my address at CommOCEAN, I outlined the importance of better understanding human behaviour in order to communicate effectively and intentionally, because behaviour and perception shape the world.

We also know that media shape perception, so the analysis of media delivery through social networks and online platforms can lead to better communication. Scientists must participate in media in order to play a part in shaping human behaviours.

Because of my training, I find the scientific approach to communication personally appealing, and so we (myself and co-author Taryn Murray, PDP Postdoctoral Fellow at the South African Institute for Aquatic Biodiversity) specifically investigated how certain information, in the form of a hashtag, spreads across the online social media platform of Twitter.

Hashtags have become markers, a method of identifying information. One can use them as bait, drawing people into a social media network that you penetrate and fill with scientific information, in a way that is easy to understand and keeps them coming back for more - and before you know it, people are hooked on your science.

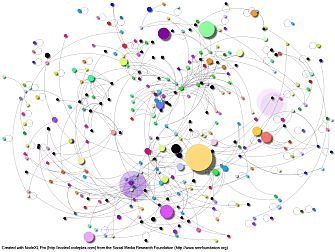

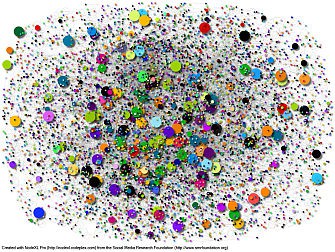

The results reveal that many marine scientists talk to each other, and form networks with each other, but even those networks are isolated from each other. So it becomes clear that marine scientists are not sufficiently reaching out to each other, we are not making sufficient global connections, and we certainly are not being as influential online as we need to be.

Our research is based on some exploratory work I did for a popular article I wrote on the subject. We compared the use of the hashtag #marinescience to the use of the hashtag #climatechange, and it is clear that in the last ten years climate change has become part of the popular lexicon.

This may initially seem self-evident, after all marine science is not an everyday term, but part of the objective of our research is to understand how the networks of the people that use these terms differ, and how we can use that knowledge to insert our marine science into everyday language and use. Even the sheer size of the networks created by people using these terms differs greatly - see the figures below for further evidence of that.

|

||||

Science communication does not, and should not, occur in a vacuum - it requires collaboration. To avoid floundering in this vast sea of information, here are some tips for a better approach to science communication:

- Begin by asking yourself what is your purpose - why are you doing this? What is your goal?

- Identify your audience. Who are you talking to? Visualise your audience.

- Why is this important? Relate to the daily lives of others.

- Become a good story teller. Stories capture, resonate. Tell simple, yet true, stories.

- Keep it simple, but not dumbed down. No one will ever complain that you have made something too easy to understand.

- Where there is any opportunity to connect, take advantage. Be interesting, or be useful, but be short. Practise your ‘elevator speech’ - can you summarise your research in two minutes?

- If you can, go for the element of surprise. Show people something they haven’t seen before. True story - this worked for me when I made a short video of a nudibranch heart beating for my own Instagram account - and it got picked up by PADI and featured on their Facebook page. Since February 21, 2017, this video has been watched over 30 thousand times.

- Engage in cheap, but effective, guerrilla marketing - target important people to penetrate the mass consciousness.

Impact

It is not enough to communicate your science, your communication must also have an impact. What is impact? Impact is having a strong effect or influence on something or someone. DO we want to change behaviour? DO we want to influence policy? DO we want to shape and increase engagement? I think the answer is YES.

We, as scientists, surely want to do all of those things, but they can only be accomplished by communicating science to all levels of stakeholders, engaging with and making the public feel like equal partners, and also by providing accessible and understandable data to those who effect change, i.e. policy-makers. We are dealing with complex problems in a complex environment, so while the answers are not simple, they are also not as difficult as they may seem.

Don’t be worried that you are the only one out there – scientists use social media all the time. This use of social media can even increase citation rates and uptake of your research (Brossard & Scheufele, 2013; Liang et al., 2014; Milkman & Berger, 2014; Peoples, Midway, Sackett, Lynch, & Cooney, 2016).

To those of you out there who simply can’t imagine adding one more task to all of the other tasks you already perform, can’t imagine learning how to navigate social media, can’t imagine why your science might be interesting to anyone else, I hear you. I really do.

Better science communication in the modern world requires all kinds of tools and skills - but your methodical and analytical training will help you with this. For some of you, there will be a steep learning curve, but then there will be rewards.

We are not just scientists - we are transformers of society, champions of diversity, levellers of playing fields, tellers of the TRUTH. If we, as individuals and institutions, are truly committed to a vision of a more equal and just society, then we have a duty to further that through our science.

One of the many beautiful things about science, for me, is that science teaches us we are not so different from each other after all. In his emails of March and April 2017, SAEON’s Managing Director Johan Pauw urged us all to become more engaged, to be better communicators, to fight misinformation.

As a first step towards achieving this, science institutions, universities, and organisations need to provide training opportunities and enable science communication to become engrained within institutional frameworks and therefore part of the mindset of scientists from the outset. Furthermore, communicating science should also be recognised as an achievement with impact.

|

In summary, I leave you with what I call the R.A.P.I.D plan for more effective, intentional, targeted, and improved science communication. Review your reasons for engaging online; Assess your tools and audience; Plan your engagement; Implement your plan; and Direct that communication intentionally and effectively.

Get out there and get your science on! #scienceiseverywhere

*If you want to know more about science communication, smart tweets, guerrilla marketing or just need some encouragement and want an introduction to social media and building an online presence, just ask!*

Further reading

- Brossard, D., & Scheufele, D. A. (2013). Science, New Media, and the Public, 339 (January), 40–42.

- Liang, X., Su, L. Y.-F., Yeo, S. K., Scheufele, D. A., Brossard, D., Xenos, M., Corley, E. A. (2014). Building Buzz. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 91(4), 772–791. http://doi.org/10.1177/1077699014550092

- Milkman, K. L., & Berger, J. (2014). The science of sharing and the sharing of science. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111(4), 13642–9. http://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1317511111

- Peoples, B. K., Midway, S. R., Sackett, D., Lynch, A., & Cooney, P. B. (2016). Twitter predicts citation rates of ecological research. PLoS ONE, 11(11), 1–11. http://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166570