Emerging researchers are equipped to become systems analysis thinkers

|

What happens when you have 27 emerging researchers, from 12 countries, and a wide variety of fields such as environmental sciences, biotechnology, medicine, engineering, and social sciences, that gather together?

I was lucky enough to attend the South African Systems Analysis Centre (SASAC) three-week programme held at Wits University (Gauteng) and Wits Rural Facility (Limpopo) during August/September this year.

We were exposed to a variety of speakers from South Africa and Europe, simulation games, a systems analysis modelling course, as well as a leadership course. One of the main goals of this programme was to equip us to become better systems analysis thinkers, and how this approach can be used to handle the complex global challenges that we face. We also had a chance to spend a day in Kruger National Park, which was an added bonus.

Not all of the lessons learnt were formally taught. Many of the skills I learnt came from spending extensive time with the participants and the visiting scientists.

|

The range of disciplines and cultures provided a platform to engage with a wide range of problems, and possible solutions, to our fields of research. I would encourage any emerging researcher (within five years of their PhD) who wants to grow their “bigger picture” view, to apply for this course next year. You won’t be disappointed.

How can we apply systems thinking?

There is no single definition that addresses all the facets of a systems approach to a particular problem. At a practical, research study level, taking a systems analysis approach will help researchers take stock of what the key variables and feedbacks are in their system of interest. Knowing what is influencing their system will inform them what needs to be studied in greater depth.

For example, how successful has the Western Cape been in managing the current drought? Their approach has been to address the crisis at a systems level. 1) The city is, for example, currently implementing alternative water sources from aquifers and desalinisation in the future. 2) They have designated more money and people to repair damaged infrastructure. 3) They have decreased water pressure (to reduce water loss through leaks). 4) They have also been tackling people’s behaviours by encouraging them to save water and use water-saving devices. But how do we know that people will change (or maintain) their consumption behaviour and attitude in the long term?

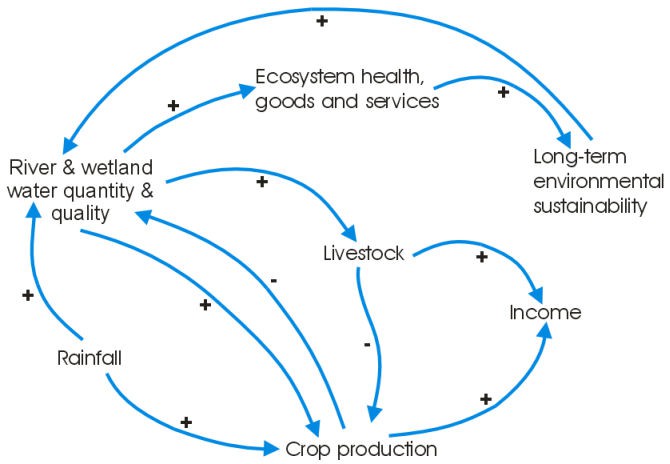

A second (simplified) example is illustrated in the figure below. In the Cape Agulhas region, rainfall has been drastically below average over the last two years, and as a result, farmers have lost a lot of income. What has caused this?

The reduced rainfall has obvious implications for the water quality and quantity in the rivers and wetlands in the region, as well as the associated plant and animal life. However, the lower water levels have also meant that salinity levels have increased, and livestock won’t drink from some of the rivers/wetlands anymore.

The farmers are now left with finding alternative sources of water for their crops and animals. In addition, they are still reliant on rainfall for their crops and grazing lands, and the lack of rainfall over the last two years has reduced the productivity of both. The reduced productivity of the grazing lands has meant that the farmers need to use a portion of the crops to feed their animals, which further reduces their ability to export their produce and obtain an income from farming.

|

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the contribution of the South African Systems Analysis Centre (SASAC), the National Research Foundation (NRF) and the Department of Science and Technology (DST) in South Africa, as well as the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), for funding this three-week programme.